Local Crossword fan readies for national competition

Source: The Virginian-PilotDate: March 4, 2014

Byline: Philip Walzer

Local Crossword fan readies for national competition

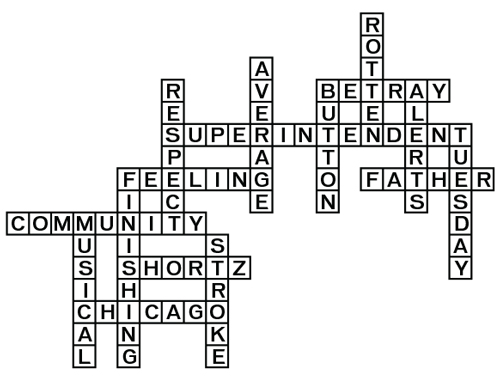

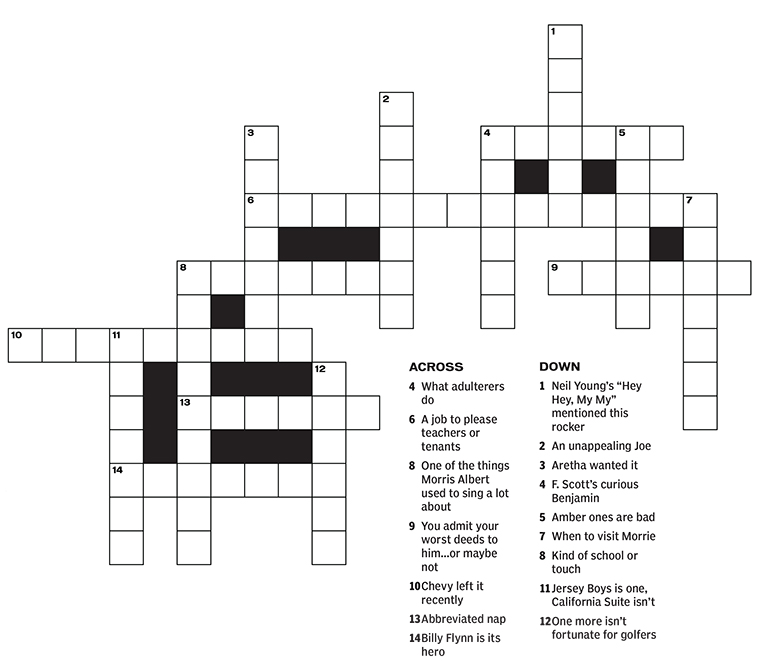

Note: Embedded in this story are 16 clues to the puzzle above. If you're not in a mood solve it, scroll to the bottom of the page to see the answers. Also,further note, this crossword violates almost every rule of puzzle construction and would not be accepted by Will Shortz or any other crossword editor. For starters, it has far too much empty space. It also is not symmetrical.

VIRGINIA BEACH

Cozying up to the breakfast bar of her home on the edge of Bay Colony, Lynn Feigenbaum switches on her laptop to start the Wednesday New York Times crossword puzzle.

Some answers come instantly. "Vermont winter destination"? Stowe. "Ungodly display"? "It could be 'impiety,' " she says.

Others elude her. "FDR's third veep"? "Yeah, right," she says.

When she gets stuck, she clicks to another section of the puzzle. Slowly the blanks get filled in, triggering brainstorms, though the midsection of the puzzle still escapes Feigenbaum.

Some of the longer answers that stymied her bring delight when she nails them. For instance, "Motivational words for a boss at layoff time?" The answer: "ready aim fire."

"That's cute," she says. "I like a puzzle that makes me laugh."

Next weekend, she'll switch back to paper puzzles and solve them silently in a far grander — and more intimidating — setting: the 18,000-square-foot, chandeliered ballroom of the New York Marriott at the Brooklyn Bridge.

Feigenbaum will join about 600 competitors in the 37th annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, founded by New York Times puzzle editor Will Shortz and made famous by the 2006 documentary "Wordplay." It'll be her 10th time there.

Last year was Feigenbaum's best showing. She finished 389th of 572 contestants, just missing placing among the top two-thirds.

That might be her high point. "I think I'm going to do (1 Down: Neil Young's "Hey Hey, My My" mentioned this rocker) this year, rottener than usual," Feigenbaum says.

To train for the tournament, she's intensified her crossword regimen from two to three a day. But "I don't sit there practicing with a stopwatch, like some people do."

Plus, Feigenbaum owns up to damaging liabilities. She doesn't have a solid handle on Roman numerals. And she's not up on popular culture or the sporting world — the source of far more clues since (13 Across: Abbreviated nap) took over the Times puzzles about 20 years ago.

When she's in the supermarket, "I take the long line so I can read People magazine," Feigenbaum says. "But it doesn't help much."

Despite those handicaps, Feigenbaum, who will turn 71 (7 Down: When to visit Morrie), is a crossword zealot. She's told her children: "This is my DNR: If I can't do The New York Times puzzle in some form, either on computer or paper, cut the cord."

Feigenbaum's bedroom shelves (4 Across: What adulterers do) her passion. Her collection includes "Kehlor Key to Crossword Puzzles" from 1933, "Word Freak," "Wordplay: The Official Companion Book" and "Banned Crosswords." (Of the last, she says, "I'm not a prude at all, but I don't care for them very much.")

Last year, Feigenbaum added her own words on the subject.

Lynn Feigenbaum of Virginia Beach is preparing for her 10th American Crossword Puzzle Tournament in New York. She prefers to work on paper but does a few New York Times puzzles online every week. (Bill Tiernan | The Virginian-Pilot)

For her master's degree in humanities from Old Dominion University, she wrote a thesis, "Crosswords at a Crossroad," covering the origins of the puzzle, which turned 100 in December; the succession of Times editors, and evolving tastes. One of Shortz's predecessors rejected a puzzle he had constructed with the answer "belly (4 Down: F. Scott's curious Benjamin)." Shortz, in contrast, has approved puzzles with such answers as "scumbag" and "man breasts."

Her title refers to a dilemma that hits close to home for Feigenbaum, a retired Virginian-Pilot editor: Print newspapers have been the main vehicle for puzzles. What happens to crosswords if they go away?

The emerging online presence of puzzles and related blogs might prove their salvation, she says. It's provided added income for The Times, which charges even subscribers for access to online puzzles. It's changed the habits of older puzzlers like Feigenbaum, who does at least two a week on her computer. More important, it's attracted younger generations.

"If they can't tweet, comment, rant and rave about a great or lousy puzzle, they're not going to have any interest in it," Feigenbaum says.

Arthur Wynne, an editor of the New York World, created the first crossword puzzle — in the shape of a diamond — as a holiday offering in the Dec. 21, 1913, issue.

The New York Times joined critics who saw it as a mindless pursuit. Feigenbaum's thesis quotes a 1924 Times editorial labeling puzzles a "form of temporary madness" and "a primitive sort of mental exercise."

The Times, though, bent to the craze and printed its first puzzle in 1942. Feigenbaum was born a year later.

Her crossword infatuation began when she was a teenager. Her family moved to Puerto Rico, where her (9 Across: You admit your worst deeds to him... or maybe not) started a furniture business. The Times was one of the few English-language papers available there. Since it didn't have any comics, she took up the crossword.

She did them on the beach — and, later, in a dull politics class at Cornell University. As a young editor in Miami, she created a puzzle packed with journalistic references — "gossip columns" was the answer to "Pillars of society" — and submitted it to The Times in 1976.

Will Weng — the editor who didn't abide Shortz's "belly button" answer — said no, citing, among other flaws, "far too many black squares." She revised it and tried Weng's successor, Eugene T. Maleska. He replied: "I am no longer accepting contributions from neophytes."

Maleska is not a beloved figure in the crossword (10 Across: Chevy left it recently), Feigenbaum says. A retired (6 Across: A job to please teachers or tenants), Maleska never let go his role as educator. The glossary in her thesis defines a "Maleska-ism" as "an obscure word that requires a dictionary."

Then came Shortz in 1993.

He received his bachelor's degree in enigmatology — the study of puzzles — from Indiana University. He then graduated from the University of Virginia's law school in 1977.

Shortz wanted to spend his life in puzzles but figured he'd need a real job at least for a few years, he told U.Va. students in a talk in 2008. He never had to work as a lawyer. He got a job with a crossword magazine, confusing the school's placement officials, who wondered why he wasn't applying to law firms.

"My (8 Across: One of the things Morris Albert used to sing a lot about) is that puzzles should reflect life and embrace everything in life," says Shortz, now 61. So Times puzzles began including brand names and references to movies, songs and sports.

His most famous one appeared on Election Day 1996. The correct answer to "Lead story in tomorrow's newspaper (!)" was "Clinton elected" — or "Bob Dole elected." "Of course, the whole election of '96 was a puzzle to me," Dole says in "Wordplay."

The movie spotlights famous puzzlers, like Clinton, who says he did hundreds as president. An athletic solver shows his daring in one (3 Down: Aretha wanted it).

"Very bravely, I'm a pen guy," former Yankees pitcher Mike Mussina says in the film. "It comes back to hurt you once in a while."

It hurt Feigenbaum too many times, so she switched to pencil a few years back. "The puzzles have gotten so tricky, and there's so much ambiguity built into every puzzle. They want you to stumble over every clue."

Recently, she began putting '50s puzzles online for a project to preserve old crosswords. The work reinforces Feigenbaum's sense of the crossword as "a time capsule of the period we live in."

Back then, a frequent answer was "Estes," for Estes Kefauver, the unsuccessful vice presidential candidate. "Today," she says, "it's Esai, for Esai Morales," the actor.

Going to the crossword tournament is like "finding your lost tribe of kindred spirits," says Amy Reynaldo, a puzzle blogger in (14 Across: Billy Flynn is its hero) who finished fifth in 2006.

The tournament, Shortz says, shatters the stereotype of puzzlers as word nerds: "To be a good crossword solver, you have to know a lot about everything — books, movies, TV, rock and roll, sports.... It's a group of smart, well-rounded, interesting, often funny people. The conversation can go in 100 different directions."

The winner for the past four years, Dan Feyer, is a New York pianist and music director in his mid-30s. Feigenbaum thinks there's probably a link between (11 Down: Jersey Boys is one, California Suite isn't) and puzzling aptitude, another reason for her pessimism.

The backgrounds of the contestants, Feigenbaum says, run a wide swath: pastor, doctor, video game creator, dog trainer.... But she acknowledges, "The nerd quotient is pretty high."

So is the incidence of fashion violations. In her thesis, Feigenbaum reports participants wearing crossword ties, hats, earrings, pajamas — even nail polish. She wears a crossword scarf she bought at the tournament a few years ago.

"Maybe if I didn't wear it, my score would go up 100 points," she says.

This year's tournament will include at least 11 contestants from Virginia. As of last week, only two from Hampton Roads had registered — Feigenbaum and Chesapeake attorney Kevin Cosgrove.

Even with no hope of winning, Feigenbaum feels a bolt of panic when the contest begins: "You've got all those bright lights, the clock ticking and Will standing there, so benignly calm."

Sitting at rectangular tables, with cardboard partitions ensuring their privacy, participants try to solve seven puzzles, some within 15 minutes. They gain points for speed and lose them for errors.

The worst is No. 5 — "the puzzle that's going to rip your heart out," Shortz warns in "Wordplay."

The top three finishers compete in an eighth round that Sunday afternoon, standing in front of the room, solving easel-size puzzles while play-by-play commentators announce their progress.

During the 2005 tournament, which forms the backbone of "Wordplay," contestant Trip Payne (5 Down: Amber ones are bad) the judges that rival Tyler Hinman was accidentally penalized in one round and Hinman's finishing time should be shortened. "It's right to get this fixed," says Payne, who eventually comes in second to Hinman.

That (12 Down: One more isn't fortunate for golfers) of sportsmanship is not unusual, says Reynaldo. "If one person has made a mistake in the scoring, someone will bring that to the attention of the judges, even if it knocks them down in the running."

Feigenbaum tries to sit at a table where the others don't cast an aura of invincibility.

That doesn't always work. In 2006, after she settled into her seat, Ken Jennings, the "Jeopardy" wiz, plopped down next to her. He ended up (8 Down: Kind of school or touch) 37th.

Feigenbaum and her roommate at the tournament, Alice Grun of Aberdeen, N.J., never sit at the same table. Grun says, "I wouldn't want to look at her smiling and raising her hand after she finishes the puzzle, while I'm tearing my hair out."

Feigenbaum is the better of the two, says Grun, who finished 444th last year.

"I think she's extremely bright, very verbal, very friendly and a fun person to be with," says Grun, 79. "If she didn't go, I suppose I would go, but it would not be nearly as much fun."

Feigenbaum's goal next week — to stay among the top 400. If not, she says, she's tempted to put the partition over her head "like a dunce cap."

Feigenbaum does an (2 Down: An unappealing Joe) of two puzzles online each week. They're usually the ones from the Monday and Tuesday Times.

Times puzzles increase in difficulty as the week goes on, and Feigenbaum can easily finish the Monday or Tuesday in one sitting at her computer. She likes to do the rest on paper because if a puzzle stumps her, she can come back to it later in the day at a Starbucks.

The "ready aim fire" Wednesday puzzle that she does online proves challenging to the end.

When she's done, the "happy pencil" doesn't pop up, meaning she's made a mistake. After a few minutes, Feigenbaum figures it out: Japan's prime minister is Abe, not Ase.

"That was more like a Thursday to me," she says.

Blogger Reynaldo also has an opinion about the puzzle.

She oversees a team of 12 puzzle reviewers who rate four to six crosswords a day on the blog "Diary of a Crossword Fiend." The blog praises the Wednesday puzzle's translation of commands into "playful nonmilitary contexts," but trashes "crosswordese," such as the answer "Omoo," a lesser-known Herman Melville novel.

"You want vocabulary, words and names that people know, not things they know only if they do crosswords," Reynaldo says in an interview.

Feeding the growth of the blogs — Reynaldo counts at least six — has been a surge of independent puzzles, most online and unaffiliated with newspapers. They don't flinch at curse words and include current musical references.

"If you've got all of these puzzles that are skewing younger, with more alternative rock and rap names..., talking about college sex hookups in a clue instead of avoiding that completely, that will speak more to people in their 20s or 30s or 40s," Reynaldo says.

The "indie" puzzles — which Feigenbaum likes, though the music clues often baffle her — have provided vigorous competition for The Times, and perhaps not just for readers.

Rex Parker, a blogger who makes Reynaldo sound like a softie, said recently that the growth of the indies has caused "a talent drain from the NYT submission pool over the past few years."

Shortz responded that the "quality of the roster" of Times crossword contributors "is quite high — although I agree the quality of the competition now is also very high.... That's great for solvers."

The growth of online puzzling has benefited The Times financially, Shortz says. An online subscription to The Times' puzzles costs $7 a month or $40 a year. Print subscribers get a 50 percent discount.

"That has literally brought in millions of dollars," Shortz says.

Many of those in the crossword vanguard, including Reynaldo, are far from down about the future.

Feigenbaum, more cautious, says, "I think they'll be here as long as I'm here." Beyond that, she's not sure.

The Times puzzle itself doesn't say much about the future.

In her thesis, Feigenbaum reports that the word "future" has appeared as an answer only once since Shortz took over. The clue, referring to a grammatical tense, was "It could be perfect."

Philip Walzer, 757-222-3864,phil.walzer@pilotonline.com